The virtual world you visit every single day, the one with your friends and family, is dead. Well, that’s according to a recently coined concept called Dead Internet Theory. In short, Dead Internet Theory presumes that:

"Large proportions of the supposedly human-produced content on the internet are actually generated by artificial intelligence networks in conjunction with paid secret media influencers in order to manufacture consumers for an increasing range of newly-normalised cultural products.”

So, the majority of your digital interaction is actually with bots or designed by bots. How true is this? Is the internet really dead?

To answer that, let me first introduce you to the self-proclaimed “best-kept secret on the internet,” the Angora Road Macintosh Café. Stylized like a relic from the early internet period, this internet café hosts an eclectic range of forum topics, from vaporwave tracks to deep philosophical discussion — an intriguing internet gem, to be sure. While you could spend countless hours browsing the forum, there is one post in particular that has caught many “normies’” (people of non-niche tastes) attention.

“Dead Internet Theory: Most of the Internet is Fake,” a thread started by IlluminatiPirate, compiles all original information about Dead Internet Theory written initially by anonymous users of 4chan’s paranormal section and another site called Wizardchan. Much of the theory revolves around manipulative government and corporate efforts to control the population, mixed with early internet nostalgia. The current internet is described as feeling “empty and devoid of people” and “devoid of content.” According to the post, “compared to the Internet of say 2007 (and beyond) the Internet of today is entirely sterile.”

The post is pretty detailed and complex, but we can break down and verify the theory into its root cause and societal effect.

“There is a large-scale, deliberate effort to manipulate culture and discourse online and in wider culture by utilising a system of bots and paid employees whose job it is to produce content and respond to content online in order to further the agenda of those they are employed by.”

We can probably agree that this occurs to some degree. I mean, you can probably think of at least one instance that you’ve witnessed in your daily browsing. And those instances are backed up with hard evidence. According to a 2021 study, 66.6% of all internet traffic is from bots — less than half of all internet traffic is from people like you and me.

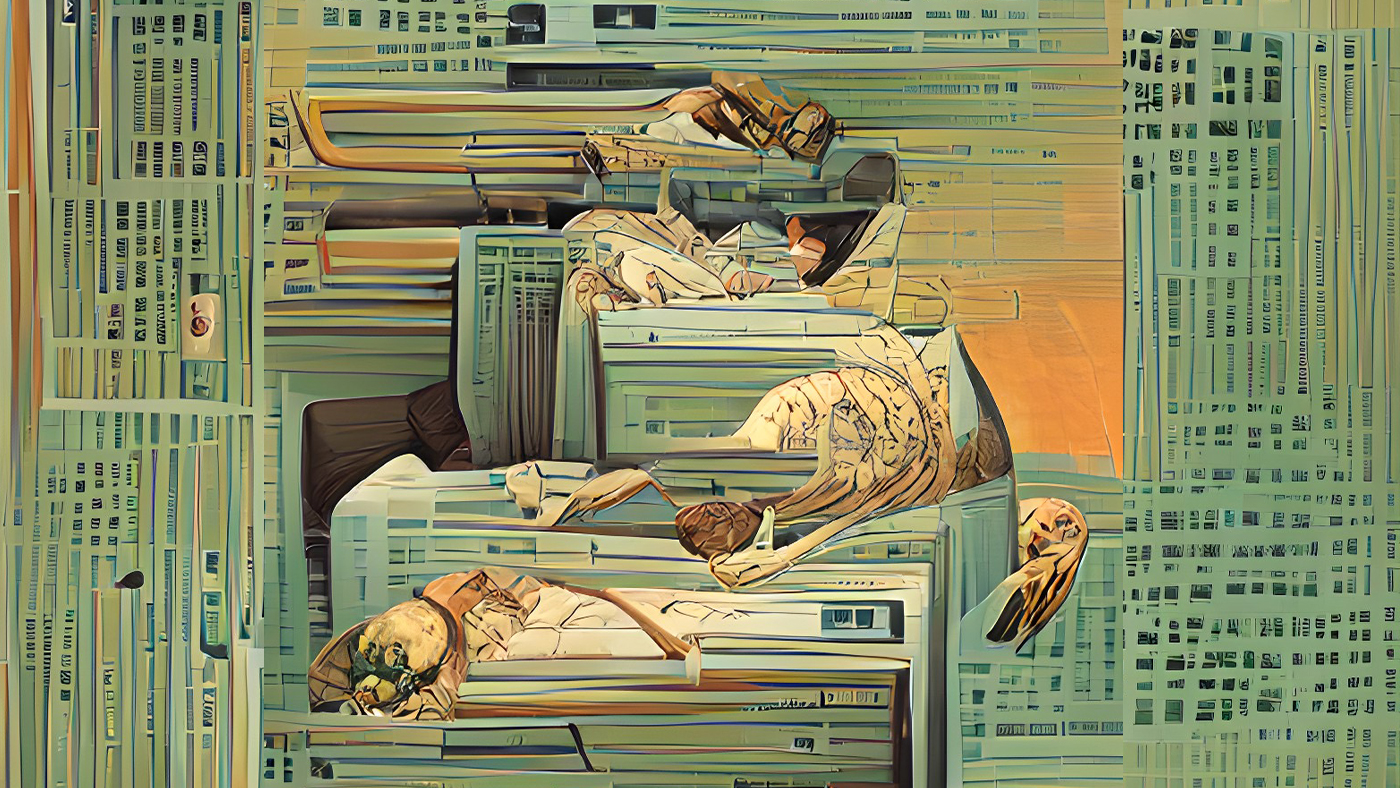

But what about the bots you don’t know about, the ones quietly generating the content you consume every day? Take a look at the artwork of this post you’re reading right now, it was all designed by an AI called WOMBO Dream. Or maybe take VentureSonic’s audio AI engine used in generating music for advertisements. The engine:

“…can create hundreds of contextualized tracks, to fit any consumer in any environment. AdsWizz clocked an impressive 238% increase in engagement for commercials using contextualized music—meaning, the listeners didn’t tune out or skip the ad.”

While making ads more appealing to everyone may be useful, these efforts have often transmogrified into something more blatantly manipulative and dismissive of users’ wellbeing — and it’s a much bigger issue than you may have thought.

In December 2020, a report exposed Facebook of telling its ad reviewers to “ignore patterns of fraud and hacked accounts as long as ‘Facebook gets paid’ with legitimate payment methods so that it isn’t on the hook for issuing refunds.” One notable example of this was in Musical.ly’s (TikTok’s precursor) Facebook ad campaign which featured young girls dancing provocatively. When Facebook employees raised concerns that the Facebook algorithm was “targeting the ads primarily toward middle-aged men, the company restricted their access to data about the ads, implied that it dismissed their concerns because Musical.ly was a big spender, and let the ads run for a year and a half.”

You can probably see why this theory contains such extreme conspiratorial claims. I mean, it’s happening right in front of our faces. All of this has got to have a severe effect on all of us, right?

“Now everyone is too cowardly to have an opinion so they copy others they like, they are more likely to follow trends and say what others said, you can also see it with the paranoia of always wanting to listen to experts.”

As further explained by the Dead Internet Theory compilation, “the internet is a fast way to get info, and info is what moves the mind, and the thing is, the mind likes recognition.” Facebook’s “likes” system was created without a negative feedback mechanic. This meant that only positive opinions could “be propagated (also accepted), and in it’s [sic] way [made] negative opinions to be obsolete.” This doesn’t mean it was intentional, but it created an extremely detrimental societal effect.

An effect that causes people, like Agora Road user Crabbelly, to “actually feel anxious about coming online now because you never know what’s around the corner, harassed/doxxed for saying the ‘wrong’ thing, smeared by the mainstream media, being hacked and spied on, there’s no separation between the internet and real life anymore and that’s a bit scary.”

And what better way to enforce the “right” thing than incorporating logic-following bots that maintain the moral rules? As writer and philosopher L. M. Sacasas explains in “Outsourcing Virtue”:

“‘…instead of solving social problems, the U.S. uses techno-fixes to bypass them, plastering the wounds instead of removing the source of injury…’ No need for good judgment, responsible governance, self-sacrifice, or mutual care if there’s an easy technological fix to ostensibly solve the problem. No need, in other words, to be good...”

Of course, every rise of a new generation sees a complementary surge in the nostalgia of the previous generation. And each surge in nostalgia has its valid points, as often the churn of human progress shortsightedly diminished what is now considered outdated.

However, nostalgia and conspiracy aside, the early internet was a freer place. There was little to no tracking, censorship was primarily relegated to the author or site moderator, and internet interactions were near exclusively human-to-human. It was authentic, maybe not hyper-personalized, but definitely more personable. This is why users have banded together to create niche, discussion-based sites like Agora Road, which can help separate themselves from “the overly saturated simulacra that the internet and life in general has become.”

It seems that with our haste in using algorithms for generating the perfect piece of content for each user, we have forgotten what it’s like to stumble upon it accidentally — to be pleasantly surprised by what we find through our explorations of the internet. We have traded authentic and serendipitous digital interactions for consistent streams of validation. Now, we are feeling the deadly side-effects and are seeking a better way.

The question is, are we too entrenched to escape? For me, that’s a resounding no. While I still use platforms like Twitter and Instagram, I go out of my way to find niche communities that have resurrected those genuine interactions or aren’t bombarded with the pressure for validation.

For me, the sheer fact that these communities and platforms even exist gives me tremendous hope for a better internet.